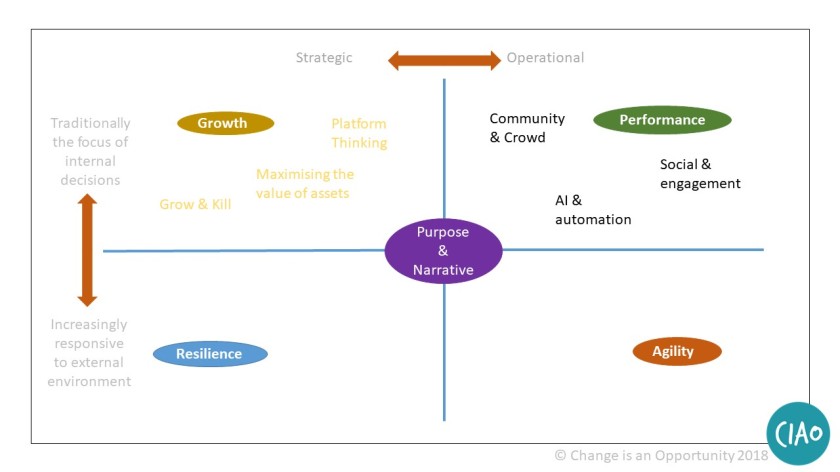

Increasingly crowds (whether existing communities or not) are a vital source of inspiration, funding, ideas, insights or simply support to many organisations. Think crowdfunding – whether the Eden project, business expansion or local causes there are now multiple ways that individuals (in a regulated manner, at least for equity and debt based funding) can get involved in supporting projects, organisations and activities that they care about. This is classic community territory where the power of ‘people like me’ turns into practical support.

But that support doesn’t have to be money – crowdsourcing has even more potential. Everything from Apple’s App Developer Network (no, they are not employees or formal suppliers) through to the employee who recommends a friend for recruitment purposes and including the ideas of the Kaggle community along the way constitute ways of tapping into communities with formal and informal knowledge, views, opinions and ideas.

The question of what’s in it for them also has multiple answers – for Apple it’s easy – 70% of any app revenue Apple takes (and by early 2019 that’s estimated to amount to some $120bn) but for others its the fun of having their ideas listened to, the intellectual challenge of a data problem, working with like minded colleagues and friends.

What underpins both, and perhaps makes any ‘crowd’ activity difficult for established businesses to identify effectively is the passion that drives these. Crowdsourcing anything requires the community or crowd to have an interest – something that inspires them to get involved. An overt outcome of making money for the organisation is certainly not enough on it’s own – but providing the value to the community is understood and engaged, it is not of itself a barrier.

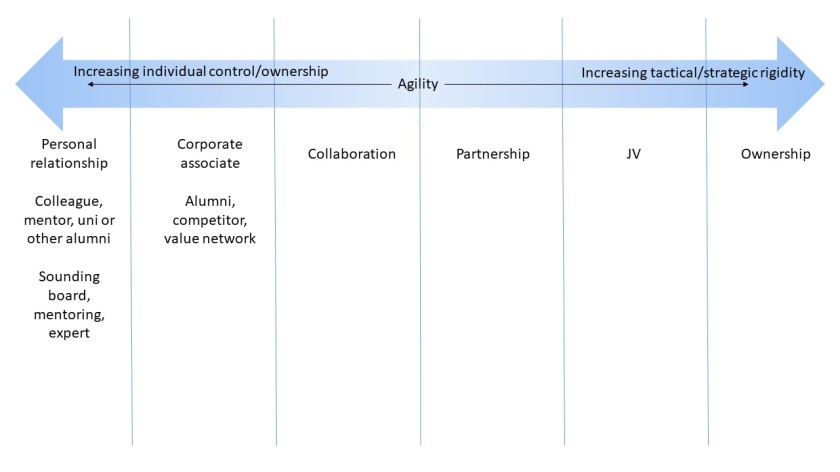

The second barrier for large organisations (and which taps into the question of agility) is the lack of command and control. The very nature of crowds are that they are not going to return the obvious – or if they are why would you bother? That can feel very risky to an organisation looking for guaranteed outcomes.

And of course from the community perspective it becomes clear that their particular crowd have an element of control, of opportunity. The increase (albeit at low levels) of peer to peer platforms to a great extent depends on communities being prepared and passionate about getting together.

Source:

Source: