For a long time economists have used long term population growth as a proxy for GDP growth – and when you consider the historic rise in global populations – especially post the industrial revolution in the 1800’s – it is easy to think that this is headed in only one direction. As the graph shows, nothing could be further from the truth if the annual growth rate is considered.

World Population 1750-2015 and projections until 2100

Source: Our World in Data

Of course this is all very long term – but it does serve to complement short term concerns about the impact of Brexit, the rise of protectionism and other mooted barriers to growth opportunities. And the concern over future growth reflects an implied view of historic growth – that the market opportunity will somehow suggest itself. From the industrial revolution onwards, through increasing globalisation and the economic rise of Australasia and South America, opportunities have continued to flow over the last couple of centuries. But several years ago a KPMG review of the fund management business pointed out that irrespective of whether or not Gen Y ever developed the investment habits of their baby boomer parents, their financial situation and hence their investment opportunity was likely to be very different from that of the second half of the twentieth century. A salutary reminder that markets shift, and a point not restricted to the investment sector.

But that doesn’t mean that growth isn’t available – simply that different mechanics are needed to achieve it. I can’t think of a clearer instance of the problems of assuming that the future of any business lies in incrementing yesterday’s model than in the question of growth.

If the barrier on overall success factors is structurally related – what about growth? To my mind this is much more a mindset issue. At the risk of oversimplifying, the opportunities provided by the rise of globalisation, benign trading conditions and the increasing affluence of the second part of the twentieth century has to some extent bred a risk aversion mindset – it seems to me that to think of growth, the market opportunity needs to be familiar, incremental (even if it is in a new geographic area) and above all proven and predictable. Two of the most famous examples of corporate failures – eg Kodak and Blockbuster both illustrate this reluctance to truly deviate from the known and proven. That mindset by the way is not necessarily limited to an organisation’s leadership – many public markets, investor communities and funders appear to have built their models on similar assumptions.

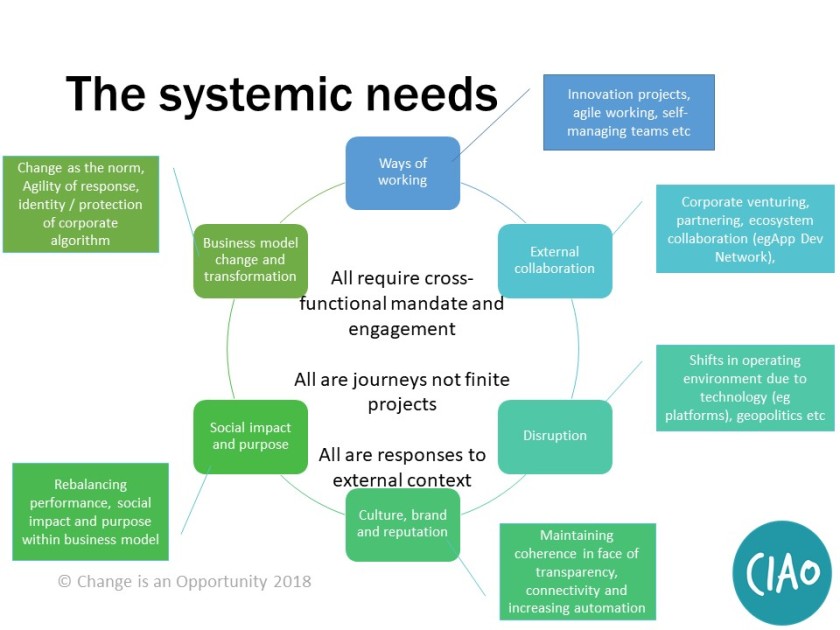

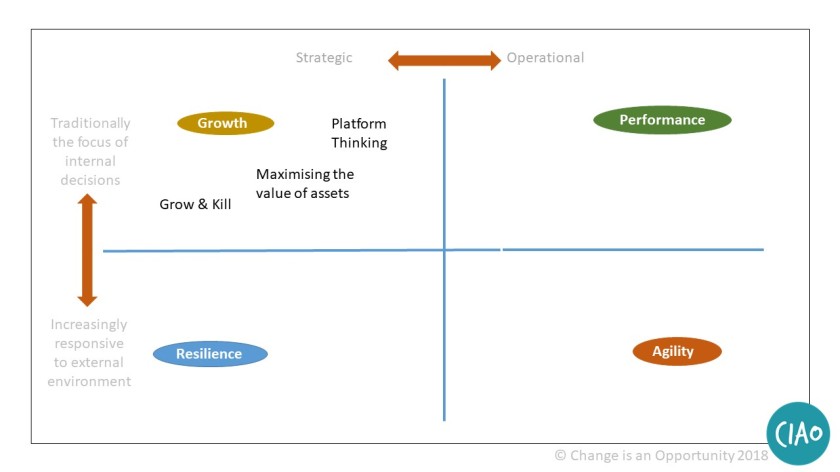

OK, so what? All of that is much better documented elsewhere. But to my mind it’s this risk aversion that makes growth today seem more problematic than perhaps it should be (I am however not suggesting that any growth is ‘easy’!). At least 3 potential strategies (and there are, and will be, others) are available but all require a different perspective as start point – one much more prepared to see the historic success as the least likely to succeed in tomorrow’s world and more prepared to consider unproven alternatives:

Source:

Source: