We all know about performance – it’s probably the commonest metric apart from cash in any business. And there are usually two elements to it – increase the top line, and reduce the costs. Both feel like an ongoing battle usually, and for most businesses both are only achieved incrementally and not always consistently.

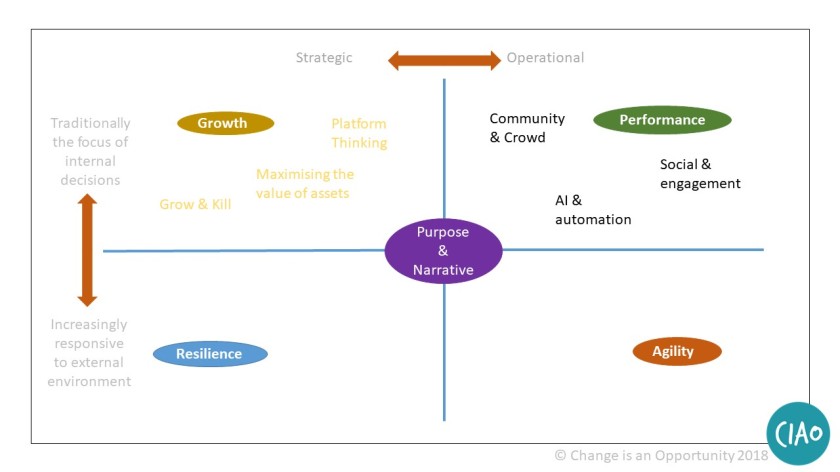

Exponential type organisations by definition don’t simply grow incrementally – so what are they doing differently? Well in many cases they are changing the fundamental rules of the game. The costs to increase the top line may no longer rest within the organisation for example. A classic example is user generated content for advertising – you don’t have to pay an expensive media company for the film, and there is (if done well and genuinely) the added bonus that other customers will tend to believe ‘someone like them’ more than you telling them. That example relates to two of the headings in the map above – community & crowd and social / engagement. Product development by your customers (Threadless involving their ecosystem in the design of T-shirts is a well known example) is a great instance of community / crowd as are many examples of open innovation – whether the long established Innocentive or individual competitions like Nokia’s one in. The key to all of these is that the cost is low (and the scaling cost nominal) whilst the benefit can be substantial and will be innately relevant. Because of the low cost, they are inherently agile, as they are both variable costs and (although there are pitfalls to engaging external audience and then not following through) very flexible.

AND they are not limited to high growth or start up businesses.

Automation and AI are slightly different (although both can be applied to reduce still further the costs of engaging audiences beyond the corporate boundary. But both have the same potential of reducing costs / improving productivity beyond the purely incremental. One simple example is the use of robots in industrial complexes or warehouses to work 24/7 – perhaps stacking parts or stock ready for human intervention during the day.

A final point – just as demonstrated by Amazon so clearly, the use of online connectivity can make the long tail as profitable to service as the mass volume sales, and increasingly connectivity, mobile and an ever expanding set of technologies are enabling:

- greater visibility and reach for lower or nil cost

- higher engagement and opportunity to involve customers and audiences

- lower production, supply and delivery costs

Clearly none of these is without issues – but in worrying about growth prospects, it’s easy to miss the startlingly large consequences of these opportunities.